Should You Listen to Your Anger?

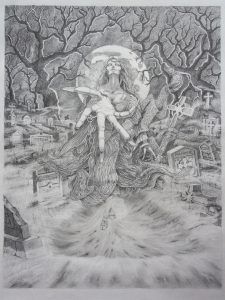

In a world where humans continually forgo the responsibility to respect other beings, rage can be a close companion. It is a sane response to an insane society.

Anger. Resentment. Wrath. Out of all the “negative emotions,” this sacred rage has an effect that accelerates our energy, stimulates the body, and thrums with an ancient power demanding that we act.

I refer to this emotion as sacred rage. This is because I don’t perceive this anger as something to be ashamed of, controlled, smothered, or otherwise discarded. I believe this to be a deep-seated rage emerging from archaic values that have been violated; I believe it is one of our most potent catalysts for change.

As sociologist Martha Beck says, “Resentment and anger are your best friends because they’re sharply pointing to the places where your freedom is most constrained.”

I believe rage to be sacred because it is the oldest compass we know and it is telling us something we need to hear.

Is The Goal to Control Your Anger?

When something happens that puts us in touch with our rage, the physical response we feel is our body telling us that something is fundamentally wrong and must be corrected.

And so, we must listen.

To be clear, in this article, I’m not relating sacred rage to folks with diagnosable anger management issues. I’m not relating this to the triggered, defensive-anger response some of us experience whenever we perceive criticism or threat.

I’m relating the concept of sacred rage to everyday people who notice the routine subjugations, shortcomings, and violence perpetuated by corporations, governments, or even people around us that create a scarier world.

I’m speaking to folks who witness the injustices waged against their neighbors, loved ones, old-growth redwoods, yellow-banded bumble bees, greater long-nosed bats, and all the other beings who make this Earth an oasis. I’m speaking to people who are watching the atrocities rippling across the globe and in their own lives.

With this context in mind, I’m not going to explain how to control the rage that results from this witnessing. I believe if you attempt to completely control this anger, it will simply be compartmentalized until it leaks out into different aspects of your life.

I can only speak from my personal experience, and my experience has shown me that rage must be listened to, channeled, and released through physical movement and fair action.

Particularly in American culture, we are taught that anger is unbecoming, something that is released through harmful, unconscious bursts or simply suppressed. So if we’re to begin this process of offering rage a seat at our table, it will require some deconditioning on our part.

If you find it difficult to make space for your rage, look to nature for examples of this. Does a volcano think twice before erupting? Does a wildfire fear spreading? Does a storm apologize for its torrents? It feels to me that, in her own way, Earth is expressing rage for the way she has been treated. Thus, the climate crisis is a demand for radical change in our human understanding of reciprocity and relationship in light of the Earth’s demands for respect.

What is Behind the Rage?

You may wake up one morning with an uneasy feeling about the day’s work ahead, even though your job is the same as it’s always been. After peeling back layers of those emotions, you may realize your rage is actually directed at grind culture as a whole, for indoctrinating you to prioritize time spent propelling capitalism over time spent with the people and passions that make you feel alive.

Or you may experience rage from a relatively small, annoying interaction with a friend, only to realize that that little interaction reflected a wider pattern of harm you experienced before you had the language to articulate it.

Rage, like trauma and so many other human experiences, is cyclical.

Just because something difficult happened on Monday doesn’t mean you’ll be processing and acting upon it by Friday. It’s okay if this process doesn’t unfold in a chronological, quick, or rational fashion. What is important is that you are able to recognize rage even in its small disguises, listen to it, and discover what personal actions can be taken to right the wrong that ignited it.

If we didn’t have deep relationships with others, we wouldn’t experience sacred rage. If we lived without empathy, we wouldn’t experience sacred rage. If we didn’t care about our personal well-being, we wouldn’t experience sacred rage.

Rage arises because the protector aspect of ourselves refuses to see harm done without retribution or realignment. Rage is born out of a fierce love for that which we value. Think about that. Isn’t it powerful?

Rage means we are still awake; we are still alive; we still care. It is an unflinching reminder of what makes us most human, and it should be given space as such.

How Do You Process Anger?

Out of all the emotions, I’ve found that rage requires physical release in order to be integrated into our minds and bodies. Rationalization and time are not always enough to metabolize it.

In ancient Greece, funeral games were hosted after the death of community members. These athletic competitions served as a public outlet for grief, allowing participants to honor the deceased through interpersonal connection and exertion. ¹

In Gaelic Celtic traditions, when a loved one died, it was customary for those closest to the deceased – typically women – to engage in a grief ritual known as keening. They would cry, lament, mourn, sing, or wail for the dead. This practice started declining in the 18th century, as the Christian church considered the uncontrolled outpouring of grief to be un-Christian and inappropriate. ²

In “Of the Sorrow Songs,” from the Souls of Black Folk, sociologist W.E.B. Du Bois studies the African American folksongs and spirituals sung during the period of slavery. Often brutal and poetic, these songs offered a safe, communal container for enslaved people to express their experiences of injustice, pain, and hope. ³

Though more examples exist, I include these to remind myself and our American audience that it’s only a recent concept that we don’t need supportive rituals, contexts, or communities to hold us in our rage and grief.

Releasing Anger Safely

Finding safe communal outlets to experience your rage can be incredibly helpful, especially when holding space with others who have been through a similar experience. The Resilient Activist’s monthly Climate Café Gatherings are supportive spaces for folks to share their difficult emotions around the climate crisis, listen to others, and share valuable insights, along with helpful facilitators including a Climate-Aware Therapist.

When you feel that sacred rage churning and burning inside your gut, know that your body is still on your side and that it can help move you through this experience.

Find an outlet. Hit what is soft and difficult to harm, like a pillow or a blanket. Go outside. Exercise. Run. Scream. Sing. Kneel. Put your hands on the Earth. Speak your truth to the soil. Release everything that has been pent up in the smallness of your body. Perform rituals of release that speak to you.

How Do You Integrate Anger?

After physically expressing your rage, you’ll eventually come to a point when you feel more capable of discerning what actions can be taken to correct wrongs. This can take some time to define, as it is whatever feels most right for you.

Your integration can look like asking for what you need without flinching. It can look like having vulnerable conversations with family or friends, and letting go of what no longer deserves your time; it can look like redirecting resources towards a cause you’re personally connected to; it can look like writing a brutally honest letter no one but you will ever read; it can look like a public statement of rage, love, accountability, or a song of rebellion so irresistible it wakes even the most weary among us.

The Value of Healthy, Productive Conflict

For many, the process of integrating one’s anger can seem like initiating difficult conversations with those who affected them deeply in a situation. Journalist and author of High Conflict: Why We Get Trapped and How We Get Out Amanda Ripley outlines the pertinent difference between “high conflict” and “good conflict.” ⁴

When we’re in high conflict with others, it feels like conflict for conflict’s sake. Markers of “high conflict” include distortion of perspective, escalation, absolutist thinking, righteousness, predictability, and stagnation. On the other hand, when we’re in “good conflict” with others, it can feel like anger, frustration, moments of surprise, sadness, flashes of curiosity, and a sense of movement. While you may not know where this argument is leading you, it’s leading you somewhere – and that’s what’s important.

While your integration of rage could alternatively be solitary, know you are not the only one engaging in this vital undertaking. Countless others are taking part in this process, however invisibly. This process of integration of rage is actually a force for good – it shocks us out of passivity and into the radical empowerment necessary to create a more honest, vibrant, and just world.

The more we acknowledge our sacred rage with the respect it merits, the fuller our cup will be when we return to everyday life, brimming with knowledge and ready to weave new threads of change.

Do not apologize for your rage.

Let it breathe through you and, in so doing, transform you.

Citations:

¹ Gill, N.S. Ancient Olympics – Games, Ritual, and Warfare

² McCoy, Narelle. Madwoman, Banshee, Shaman: Gender, Changing Performance Contexts and the Irish Wake Ritual

³ Du Bois, W.E.B. “Of the Sorrow Songs,” from The Souls of Black Folk

⁴ Ripley, Amanda. High conflict: Why we get trapped and how we get out