Ask a Resilient Activist article by guest writer, Anna Woiwood

When Urbanization Excludes, Instead of Connects

Perhaps every generation feels as if they arrived into a world of decline, but I feel it very acutely. When I look at the cities around me they appear broken and shattered. Once intricately designed, walkable cities, many have fallen into disrepair or are torn down and patched over with steel towers and parking lots. There’s a lack of character, of cohesion to it all.

The true problem, however, rests in the fact that the modern city is no longer built for the pedestrian, but for the car.

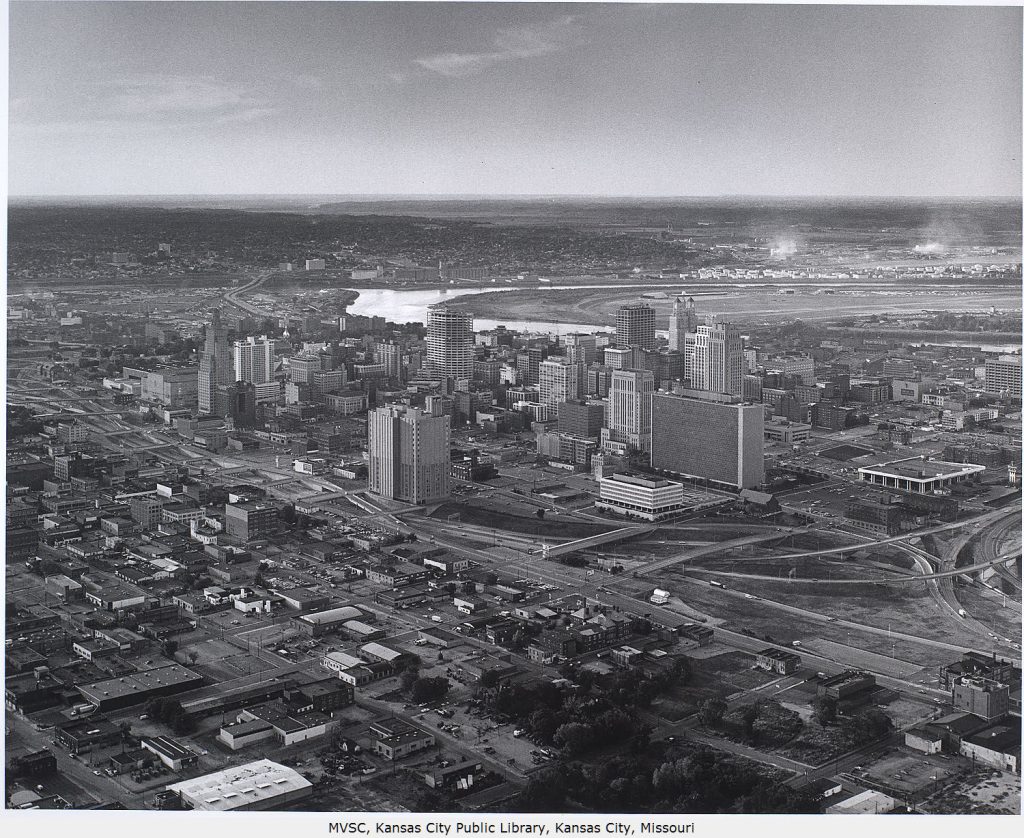

Kansas City is one such town where you can see the visible scars of a once-robust, walkable city.

I see it on my commute down US-71. Glancing off the highway, one finds the remnants of once thriving suburban areas. The parallel streets half-lined with falling apart homes, the roads now intercepted and chopped off by the meandering byway. In the late 1960s, nearly 2,000 homes were demolished in this eastside corridor to make way for a freeway that would connect distant, primarily white suburbs, to the downtown business district.

This massacre of homes was another wound in the side of a community already ravished by racial segregation and redlining.

Kansas City’s Urbanization and Colonization

We cannot talk about the building of American cities without acknowledging the land and racial injustices upon which they are formed.

European settlers arrived with the intent to conquer and own land, to take it for themselves, to do with as they pleased. They did not have the same regard as Natives toward the bond between humans and nature; European settlers cared little for preserving the natural resources in the area.

The junction of the Missouri and Kansas Rivers provided an ideal area for early Native tribes because it provided the right climate for producing food, as well as river access for trade and transportation. The presence of Osage communities date back almost 10,000 years in this region, as well as the Kaw, Kickapoo, Shawnee, Delaware, Wyandotte, and Kaskaskia people.

It was early European exploration and a thriving French fur trade along the Missouri River that drove non-Natives to this area, and as Europeans discovered the fertile soil here, they began to form towns and force the Native people off the land. These early Native tribes are remembered now in names of local streets and counties.

The city of Kansas City formed during the rocky times of the Civil War, at the juncture of Missouri (a slave state) and Kansas (a free state). The city was split in half, communities warring against one another in bloody battles (the site of once such major battle now the idyllic Loose Park south of the Plaza).

These racial lines remain if one peers down Troost Avenue. Largely driven by the early suburban developer J.C. Nichols, this man purchased land and made it illegal for anyone of color to purchase a home in the westward subdivisions (such covenants have been made illegal, but remain in the wording of deeds to this day).

This planned segregation has had profound impacts on the city today.

As stated in the 1947 City Plan for Kansas City, “It is common experience that the maximum long-range residential values can be secured when areas of homes with a high degree of similarity are segregated from those of other characteristics.”

This led to disinvestment in certain areas, and over-investment in others. Forcing non-white students into certain schools and then disinvesting in those schools led to many public school closures in the area. Yet, the wealthy, white areas remain well-invested with a plethora of public and private school options.

This disinvestment helped create areas that are cut off from the heart of the once walkable city, separated from resources vital to thriving neighborhoods.

It is man’s need for forward progress and the prioritization of cars over pedestrians that have gotten us to this point.

The Cable Streetcar System: A City’s Lifeblood

Kansas City bloomed as a city in the late 1800s. From time-to-time, you can see the skeleton of this city in the beautiful architecture that remains from this early era.

What has not been torn down and replaced with bland modern buildings, tells the story of a once thriving city.

If you walk down the sidewalk and look up, you can still spot the painted signs of the past – such as a fireproof hotel on Delaware, the Drum Room advertised at the President Hotel, hardware stores, printing buildings – all remnants of a once-dynamic and industrial city.

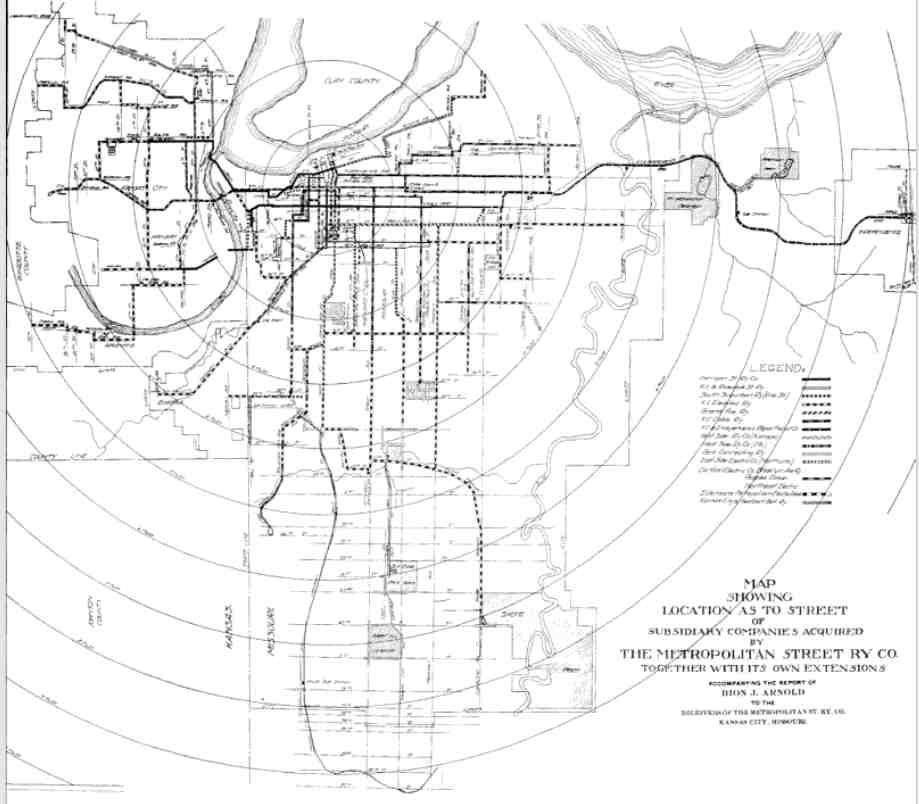

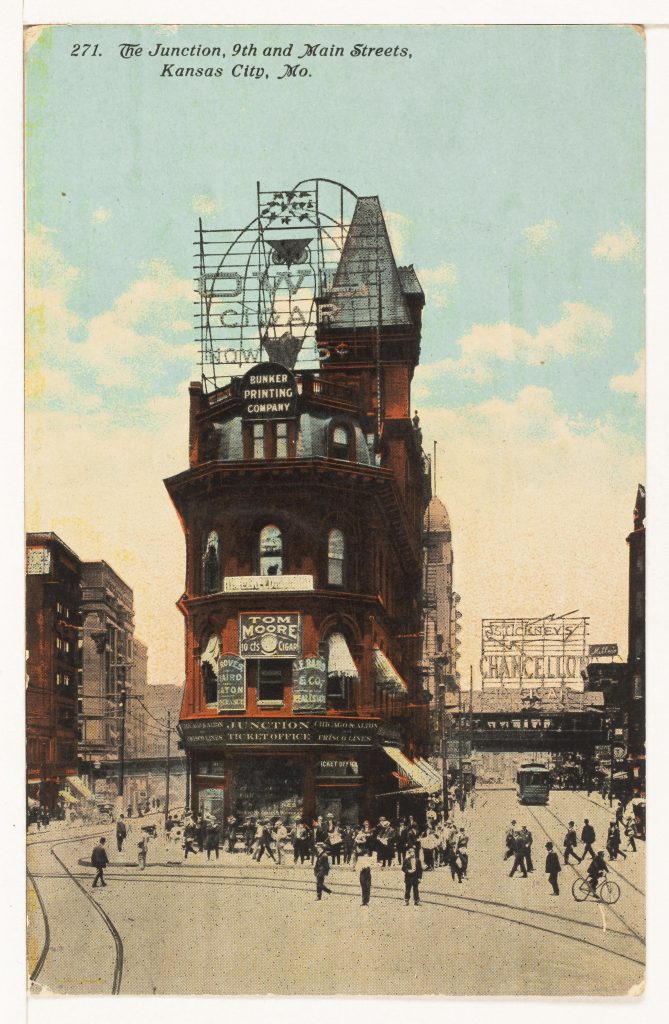

What made Kansas City especially vital was its robust and intricate transit system. In the late 1880s, cable streetcars emerged.

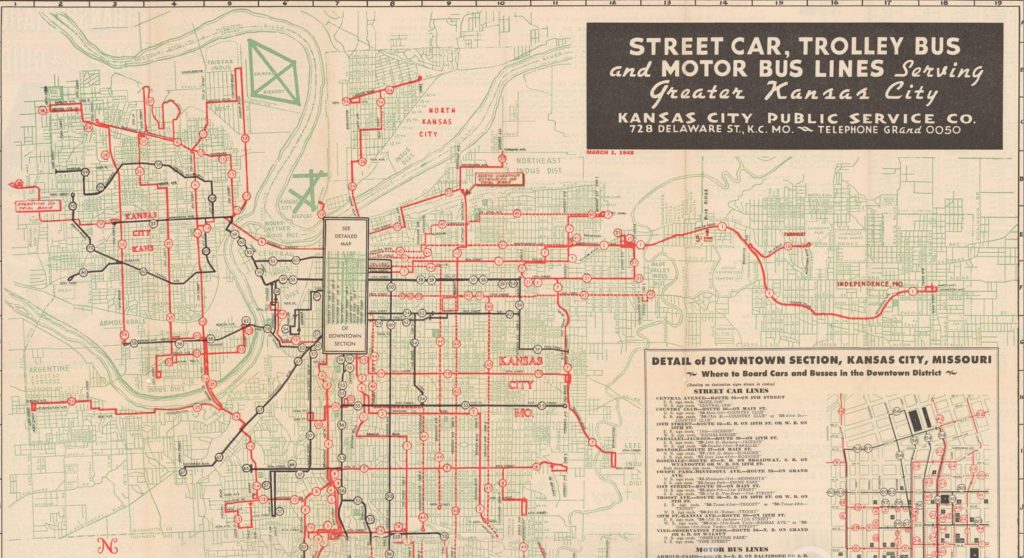

By 1912, ridership for the year reached 120 million fare-paying riders. The streetcar system was intricate, with lines moving in all directions through the grid of the city.

In 1912, the lines extended all the way northwest to Brown Avenue in the Quindaro neighborhood of Kansas, west to Rosedale in Kansas, as far northeast as Independence, and as far south as 87th and Prospect.

The streetcar was even able to traverse the cliffs in the northern part of downtown, carrying passengers down to the West Bottoms Manufacturing District on the 9th Street Incline.

The Kansas City streetcar system was one of the most extensive cable car systems in the country – comparable to systems used in San Francisco, New York City, and Los Angeles.

How Cities Turned from Walkable to Car-Dependent

A change came in 1912 that led to the electrification of the streetcar system. This modern upgrade was safer and less accident-prone and far more comfortable for riders, according to Michael Wells, senior librarian for the Missouri Valley Special Collections at the Kansas City Public Library.

The lines originally were all operated by individual companies, but by 1916 they had consolidated into The Kansas City Public Service Company.

With this consolidation of ownership and impact of the Great Depression in the 1920s, the tides began to turn away from the streetcar system.

The company found that they could replace streetcars with buses to cut costs. By 1924, motor buses were introduced as an additional form of transportation to aid in lines that the streetcar did not make.This led to the decline of people-centered infrastructure, in favor of automobiles.

Emerging car owners’ desire for rapid city travel contributed to the push for disinvestment, and the move away from walkable cities.

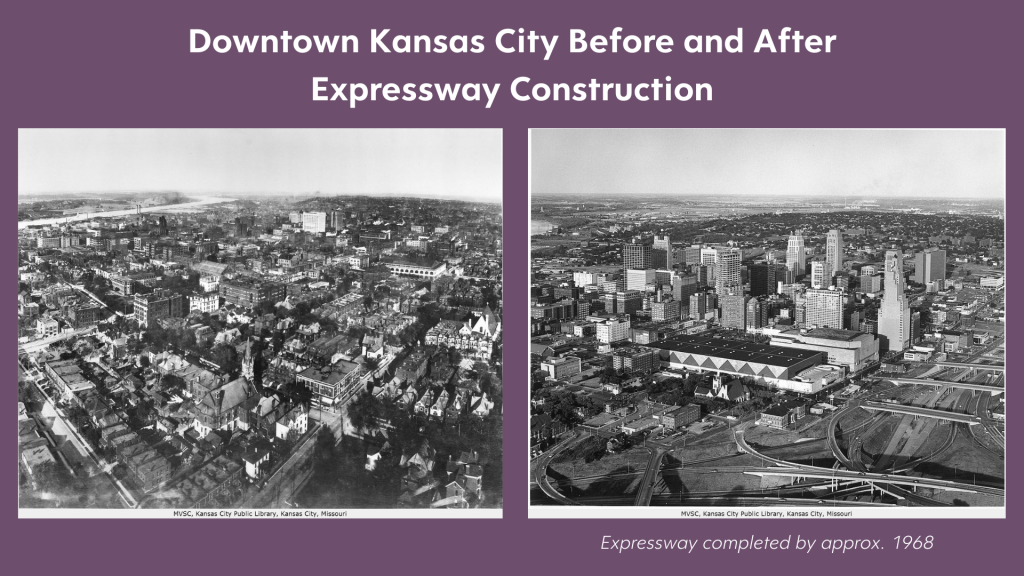

To prioritize vehicles, new freeways and roadways would need to be laid to help move traffic along.

Kansas City had always been a transit-friendly, walkable city built for the pedestrian. Now, it would need to support infrastructure for those wealthy enough to own a personal motor vehicle.

By 1944, the transit system offered streetcar, trolley, and bus lines. In 1951, an engineering report emerged that boasted the benefits of expressways for the city.

By 1957, we lost the streetcar entirely, with the promise of new and improved highway systems.

An article in The Kansas City Star from June of 1957 stated, “A quarter of a century ago, Kansas City had 800 street cars. For the rest of this week it will have 41. Next Sunday, all will be gone.”

Kansas City’s Transportation Challenges

Today, a new streetcar operates in Kansas City. With a grand opening on May 6, 2016, the KC Streetcar traverses north from Union Station toward a loop around the River Market on a two-mile route. At its peak, the former Kansas City streetcar system spanned over 300 miles. Soon, this new KC Streetcar line will extend down Main Street to the Plaza and the University of Missouri – Kansas City, adding three and a half miles to the route. Ridership is free, though access to this public transportation is limited to the downtown area.

What have we lost since the turn of the last century?

One of the features the highway system boasted was a loop around downtown Kansas City. This flow of traffic intended to improve access to the businesses there by car. However, the demolition of thousands of homes and businesses to create this highway system did little to help the populace.

By strangling downtown with freeways, it cut off the free flow of pedestrian traffic. It removed homes from the area, forcing people to live further away and rely on cars or buses to enter the city.

It broke apart previously thriving neighborhoods, so that now if you travel east or northeast from downtown, you see broken-down communities with rundown homes, boarded-up apartment buildings, and the absence of grocery stores and other necessities. The area is no longer pedestrian-safe. Many people are forced to rely on the bus system, which is not dependable. In fact, as of 2025, funding for the public bus system was cut, leading to the loss of nearly half the existing routes.

This strangulation of a once pedestrian-friendly city has led to higher crime rates and failing businesses.

Prospect Boulevard was once a thriving community, connecting the city north to south. Driving along the street today, one can hardly fathom the vibrant businesses, restaurants, and community centers that were owned primarily by African Americans. When US-71 was instated through the eastside, it removed the travel from Prospect Boulevard, causing a decrease in traffic and urban relevance.

The racial lines remain from the Civil War era, as the city continues to invest less in public infrastructure and communities in the east (despite government tax incentives that are aimed to help the central city region), and more in luxury apartments along the current KC Streetcar line and privatized investments that do not help those struggling to make ends meet in an increasingly expensive city.

Community, Accessibility, and Sustainability: The Benefits of Walkable Cities

I think, too, of the environmental impact all of this has on the city. Sitting in traffic on my way home from work on US-71, I think of how these neighboring homes are affected by pollution from the freeway. I imagine, instead of standstill traffic filling the air with toxic fumes, a light rail train that could travel from the heart of the city out to Independence, to Parkville, to Overland Park, to Lee’s Summit, to…

I once lived in New York City and commuted daily on the subway. I miss the time I had to read. I miss the ability to avoid contributing to the CO2 emissions. I miss being able to bike easily through the city to work. I miss walking down the streets of New York, hidden away in the flow of pedestrians, a subway station always a road or two away to travel to another part of the city.

On my breaks from work in Kansas City, I walk from the Central Public Library north across the bridge over the upper highway loop on Delaware. There is no shade and on hot summer days it’s insufferable to make this journey to the River Market area.

I walk through the junction of Main, Delaware, and 9th and think of how once this intersection was filled with people going every which way, streetcars carrying people all around the city, and the iconic Vaughan Diamond Building that once sat at the heart of this juncture.

Now, as I walk in the sweltering heat, I look up and see nothing but freeways and roads, empty parking lots, and the outline of historic buildings that have not fallen to luxury apartments in the River Market.

In the place about where the iconic Vaughan Diamond Building once provided an eyecatching focal point, the FlashCube Luxury Apartment building now fades into the sky. A square building covered in mirrored windows, the FlashCube Luxury Apartments has one of the highest rates of killing birds because of its deceptive surface.

The way a city is built impacts not only humans, but animals alike. Creating buildings that are more ecologically and environmentally friendly is a necessity. Bringing back greenery – on sidewalks and incorporated into buildings – would help decrease heat, give animals a place to hide, and offer resources to use. This benefits everyone.

If we are to create more equitable, eco-friendly, walkable cities, we must invest in public infrastructure again.

When people no longer have to invest in cars, what might that extra money do for them?

If we reinvest in building walkable communities, what new businesses might spring up to support such communities? The possibilities are endless for this ever-evolving city, but I believe we might need to travel backward in time and recreate Kansas City as it once was—a dynamic, pedestrian-friendly town.

Dividing Lines: A History of Segregation in Kansas City is a publicly available “driving audio tour” anyone can listen to while exploring Kansas City by car. The audio article discusses JC Nichols, a real estate developer whose business practices (including racial covenants in deeds) helped institutionalize and spread residential segregation practices. Sadly, Kansas City is a major birthplace of redlining, and this driving audio tour provides a thorough visual and historical explanation of its impact on the city, as well as how JC Nichols institutionalized it this practice during his tenure with the Federal Housing Administration.

If you’re interested in learning more about Kansas City’s history firsthand, consider joining Urban Hikes KC for one of their upcoming community walks through the city. These walks blend history, exercise, story-telling, and community.

In her last contribution to our Ask a Resilient Activist column, Anna Woiwood’s The Dream City crafted a striking vision of sustainability in our cities. Instead of the usual focus on rural utopias, Woiwood reminds us that urban spaces deserve our imagination too —and designing those sustainable, walkable cities may just be key to our future.