“Each January, I am overwhelmed by the pressure of New Year’s resolutions. There is such a heavy expectation entwined with these goals; they state a message that says ‘Your current existence is flawed, and you need to do better. You need to work hard to improve.’

Why is our culture so quick to shame one’s flaws? Perhaps it is time to reframe this perspective to instead celebrate our imperfections, embrace our current selves with loving kindness, and grow from there. Read on to discover how one Resilient Activist community member, Michael Weir, adapted his mindset by seeking wisdom at the intersection of literature and ancient art.”

Ernest Hemingway and the Japanese art of Kintsugi (金継ぎ, or “golden joinery”) may seem like strange bedfellows at first glance. One is a master of minimalist prose who chronicled the struggles of humanity, while the other is a centuries-old craft that transforms broken pottery into exquisite works of art. Yet, at their core, both speak to a universal truth: our imperfections don’t diminish our worth—they make us who we are.

Let’s explore what Hemingway and Kintsugi can teach us about resilience, identity, and embracing the beauty of our broken places.

The World Breaks Everyone

Hemingway famously wrote in A Farewell to Arms:

“The world breaks everyone and afterward many are strong at the broken places.”

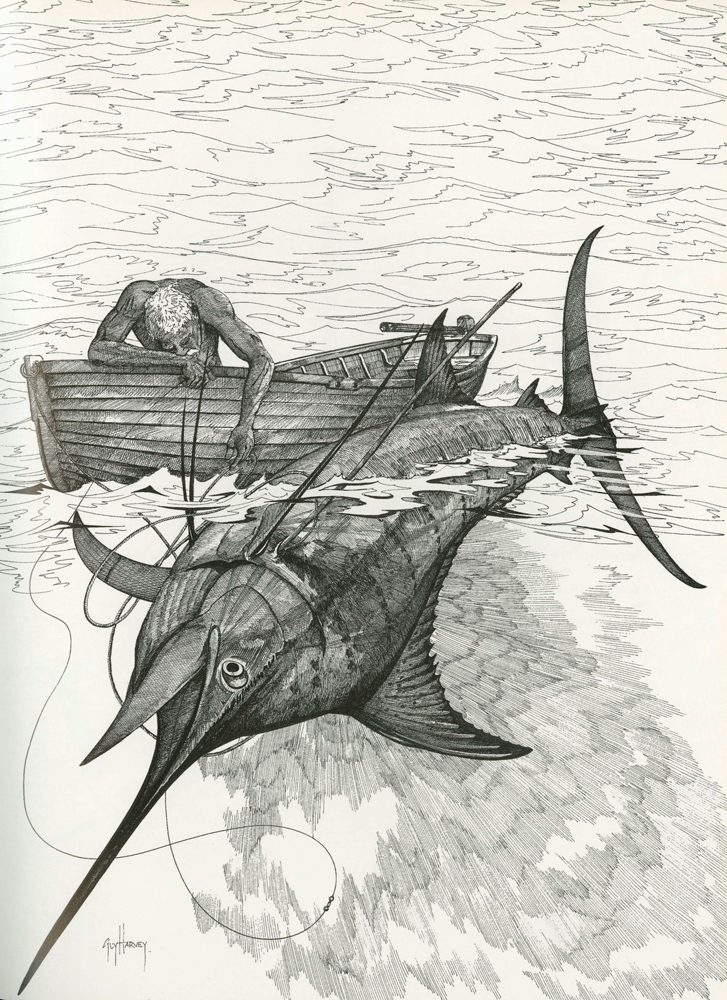

This line encapsulates his worldview. Life is relentless. We all face heartbreak, failure, and loss. Hemingway’s characters are often battered by war, love, and their own demons, but they endure. In The Old Man and the Sea, Santiago, the aging fisherman, battles the marlin for days, his hands torn and his strength waning. Even in his eventual loss, he gains something intangible: the dignity of having fought well.

Hemingway’s work reminds us that perfection is not the goal. Struggle and suffering are inevitable, but they also offer an opportunity. They shape our identities, much like the cracks in pottery.

The Golden Repair

Kintsugi offers a parallel story. When a piece of pottery breaks, traditional Kintsugi artists don’t discard the fragments or attempt to hide the damage.

Instead, they repair the cracks using lacquer mixed with powdered gold. The resulting object is not only functional again—it is more beautiful than before.

This philosophy comes from the Japanese concept of wabi-sabi, which finds beauty in imperfection, impermanence, and incompleteness. The repaired pottery doesn’t try to mask its brokenness. The gold-filled cracks highlight its history, its resilience, and its uniqueness.

Kintsugi is a metaphor for life. Like broken pottery, we are all imperfect, and that’s okay. The cracks in our lives—the mistakes, the failures, the losses—are not something to be ashamed of. They are the moments that shape us. They are our story.

Identity is a Process

If there’s one thing Hemingway’s characters and Kintsugi teach us, it’s that identity is forged in imperfection. Santiago isn’t defined by his victory or loss over the marlin—he is defined by the fight itself. Similarly, a Kintsugi bowl is not just a repaired vessel; it is a testament to the transformation that occurs when brokenness is embraced.

We often view identity as something fixed. We think, “I am this,” or “I am not that.” But the truth is, identity is a process. It is shaped by every experience, especially the difficult ones.

When we stumble or fall, we may feel like failures. Yet, these moments are when we grow. They force us to adapt, reflect, and rebuild.

The first draft of anything—a novel, a career, a life—is imperfect. Hemingway knew this well. He once said, “The first draft of anything is shit.” But he also understood that revision is where the magic happens. Just as a potter repairs a broken bowl, we refine ourselves through trial and error.

Our Strength in Brokenness

Both Hemingway and Kintsugi suggest that strength doesn’t come from avoiding pain or pretending to be flawless. Strength comes from acknowledging our cracks and choosing to fill them with something meaningful. In Hemingway’s world, this might be courage, love, or endurance. In Kintsugi, it is literal gold.

But let’s not romanticize brokenness. Being cracked isn’t fun. Santiago’s hands were bloody. Hemingway himself battled depression, addiction, and loss. And repairing a piece of pottery with Kintsugi requires patience and skill—it’s not an overnight process.

The beauty lies in the work we put into repair. Every crack, every scar, becomes a testament to our resilience. As we rebuild, we don’t just recover what was lost; we create something entirely new—something stronger, more intricate, and uniquely our own.

Embracing Imperfection

At its heart, Hemingway’s writing and Kintsugi share a simple but profound truth: we are all works in progress. Life will break us. But we can choose to repair ourselves in a way that transforms our pain into beauty.

The next time you feel broken—whether it’s a failure at work, a fractured relationship, or a personal struggle—remember that your cracks are part of your story.

They are not signs of weakness; they are proof of resilience. Like Santiago battling the marlin or a Kintsugi bowl glowing with golden veins, you are stronger because of what you’ve endured.

Hemingway’s world and the art of Kintsugi invite us to embrace imperfection as a natural part of life. Because, in the end, everything is imperfect at the start. It’s the way we repair and rebuild that defines us.

So, let your cracks show. Fill them with gold. And know that the beauty of your life lies not in its perfection, but in its resilience.