A Balm for Humans, Animals, and Ecosystems

As I made my morning Double Bergamot Earl Grey tea, I thought about all the lovely gifts a plant can bring to the world. Coming into bloom right now is Monarda fistulosa, which grows in 42 of our 48 states, blooms for about a month, and grows 2’ to 5’ tall.

It has the great quality of being tolerant of a variety of conditions, from full sun to part shade, dry to slightly wet. And like me, it prefers good air circulation.

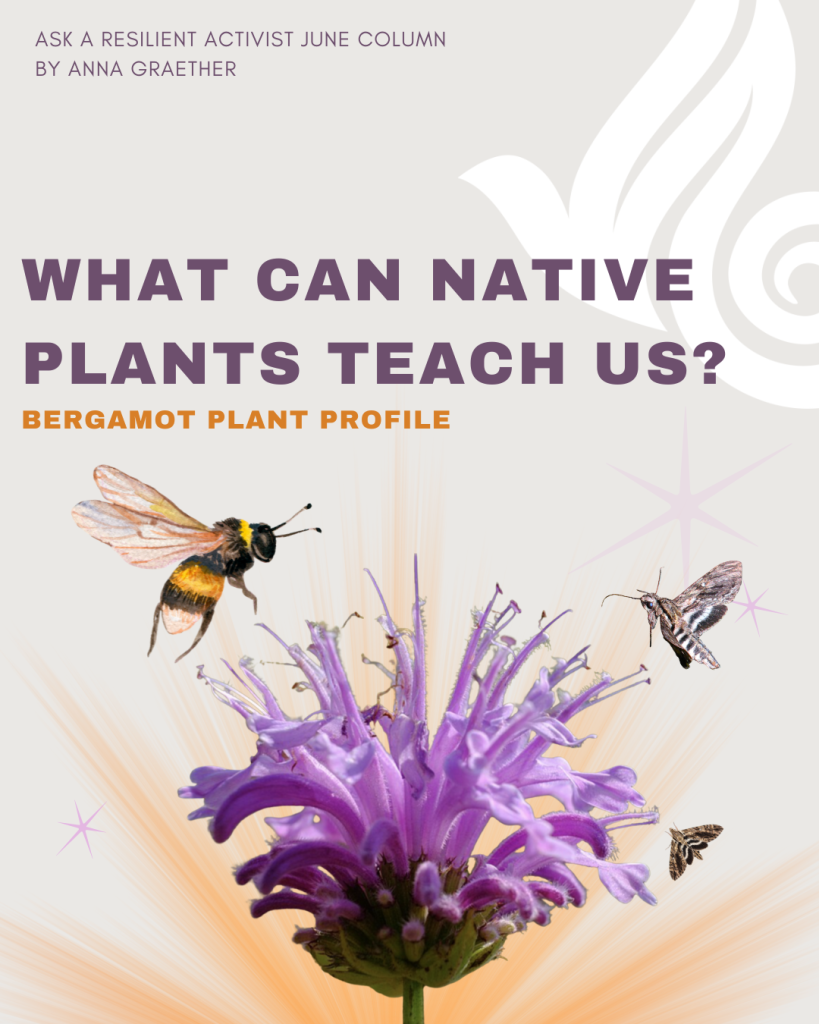

One of the best forage plants for bumble bees, Monarda fistulosa is commonly known as Wild Bergamot. It’s also sometimes called Bee Balm because it’s such a great nectar source for bees. I think it’s also a balm for me–there is nothing better to calm my soul than watching pollinators on a plant.

I thought my Earl Grey tea was made from this plant, too–wrong! While you can make tea from the leaves of this plant, the ingredient in Earl Grey tea is from Oil of Bergamot, which is a citrus fruit. Always learning.

Wild Bergamot is a highly prized nectar source, so much so that there is thievery in the ranks. Because the nectar is stored at the base of the long tubes, short-tongued bees and wasps can’t reach it. Ingenuity prevails, though, and insects like the mason wasp chew a hole at the base of the tube to get the prize.

And what’s really cool about Wild Bergamot is that its flowers open throughout the day, so as older flowers are depleted of their nectar, new ones open up…how awesome is nature.

Alliance, Coevolution, and Interdependence

Bergamot is a generous and multi-faceted plant. It offers valuable nectar to pollinators, helps stabilize soil through its deep roots, provides shelter and microhabitats for insects, increases reproduction chance of nearby native plants, and supports a higher plant-pollinator network diversity. Bergamot understands what it means to nurture community in the wider web of life.

Some insects have evolved special relationships with certain plants. When that plant is the only type an insect will use for egg-laying, it’s called a larval host. Wild Bergamot is a larval host to both the Hermit Sphinx Moth and Snout Moths.

While we are all familiar with bumblebees and honey bees, there are also over 4,000 species of native bees in the United States. Some of those are specialist bees that have a more focused dietary preference; they rely on a specific group or even a single species of plants for food. Their life cycles are finely tuned and synchronized with the blooming periods of their preferred plants.

This is an amazing adaptation that reveals the intricate co-evolution of bees and their host plants. It’s also a challenge as bloom times shift in response to climate change. For Wild Bergamot, the Black Sweat Bee is a specialist bee, attuned to its bloom time and lifecycle.

Besides this specialist bee, many medium and small bees forage for pollen on Wild Bergamot, including long-horned, cuckoo, green sweat, wool carder, small resin, and leafcutter bees.

I will need a lot more patience and much better eyesight to study these well enough to distinguish the difference. Someone who has, though, is Heather Holm, and her book Pollinators of Native Plants: Attract, Observe and Identify Pollinators and Beneficial Insects with Native Plants is a great resource.

Besides the buzz of bees, you may see the flash of butterfly wings at Wild Bergamot–the flowers attract Eastern Tiger Swallowtail, Silver Spotted Skipper, Monarch, Great Spangled Fritillary, and a number of moths including the Hummingbird Clearwing Moth pictured below.

Tomorrow I’m hoping to step on my porch with my morning cuppa and delight in the dance of life, the interplay of insects and light eaters.

I hope you’ll be doing the same in your corner of the planet.